Posted here are updates on my published research on Bernini, as new discoveries come to light. The updates make no attempt to keep abreast of all of the voluminous new Bernini bibliography, but rather focus primarily on topics and data discussed or mentioned in my books.

(By the way, the best annotated bibliography of the most essential works about Bernini is that prepared by Evonne Levy for the online “Oxford Bibliographies” [available by subscription only] — although it incorrectly states that my Bernini: His Life and His Rome is “without a scholarly apparatus:” This is simply not true; everything in the book is documented in the notes; the notes are short because in most cases all I had to do was simply refer readers to my extensively annotated edition of Domenico Bernini’s Life of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, with its 183 pages of detailed notes and a bibliography of 700 entries.)

The updates are divided among three pages:

Bernini Updates 1 = Regarding Domenico Bernini’s Life of GLB

Bernini Updates 2 = Regarding Bernini: His Life and His Rome

Bernini Updates 3 = Other New Research Discoveries & Insights

REGARDING MY EDITION OF DOMENICO BERNINI’S LIFE OF GIAN LORENZO BERNINI:

N.B. The most recent update is inserted at the beginning of this section, though still numbered consecutively in order of posting. (The last entry before April 15, 2016 is #42 at THE END. Click here for the very first entry.)

Corrections to my published text are to be found below, at entries ## 3 and 4.

A digital copy of the original 1713 edition of Domenico’s biography is available through Google Books.

Also available through Google Books is a copy of the original edition of Filippo Baldinucci’s Vita del Cavalier Gio. Lorenzo Bernino of 1682.

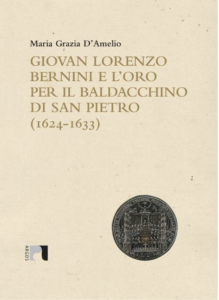

#75. New archival documentation published on the baldacchino

I would like to bring to you attention an important work, published in 2021, on Bernini’s baldacchino by Maria Grazia D’Amelio, with many new details and revelations about the project, from the moment Pope Urban decided to commission the work to the finished product:

Giovan Lorenzo Bernini e l’oro per il baldacchino di San Pietro (1624-1633)

di Maria Grazia D’Amelio, in cofanetto, I vol. 196 pp., 99 ill. col., II vol. 42 pp., Argos, Roma 2021.

You can read a review of the book (in Italian) in the online Giornale dell’Arte, Feb. 9, 2023 issue. As the reviewer remarks (my translation): “After so many studies of the baldacchino, it is surprising that significant new details have been able to be discovered.” One new detail — a major detail — regards the gilding of the finished bronze, which comes from a hitherto unpublished document of 1633 found by D’Amelio in the archives of the Fabbrica di San Pietro, “Oro messo nelli bronzi.” As the reviewer points out (my translation), this feature is no mere casual ornamentation; instead, “the gilding serves a strategic role on the baldacchino inasmuch as it provides a contrast between the dark tones of the bronze and the brilliant luster of the gold, ‘carefully calibrated to the variations of light within the transept’ with the aim of ‘activating a dynamic optical effect upon the surface of work by means of the spiraling of the columns which closely interact with the ever changing effects of the natural light.’”

#74. The Capra Amaltea is NOT by Bernini, reports Anna Coliva; Andrea Bacchi’s questioning of the attribution already in 2009

Here is former Galleria Borghese director Anna Coliva’s entry on the Capra Amaltea in vol. 1 (cat. 41) of the 2022 Catalogo generale of the Galleria Borghese, edited by Coliva in which she argues in very detailed and persuasive fashion against the Bernini attribution on both stylistic, technical, and historical (documentary) grounds. (See my Update #10 below for more on this work, long considered Bernini’s first solo piece.)

Note that the only contemporary source to attribute the work to Bernini is Joachim von Sandrart in 1675, an attribution not given any scholarly credence until 1926 by Roberto Longhi but thereafter accepted virtually universally, until 2009 when Andrea Bacchi questioned the attribution on stylistic grounds in his article [ Bacchi 2009 Bernini e gli scultori ] “Bernini e gli scultori del suo tempo,” in “Aus aller Herren Länder: die Künstler der ‘Teutschen Academie’ von Joachim von Sandrart,” eds. S. Meurer, A. Schreurs-Morét, L. Simonato (Turnhout, Brepolis, 2015, pp. 141-153). Bacchi points out what is visually obvious: the Capra amaltea is incongruous stylistically with what is known about Bernini’s earliest works, especially the influence of the style of his father Pietro. As for Sandrart’s credibility — which, I have noticed, is simply accepted as a given truth by art historians who have never taken the time to examine critically the German art historian’s text — Bacchi has this to say (2009, p. 144, my translation, emphasis added):

“By itself, the eyewitness account of Sandrart, however authoritative he may be, cannot be considered the definitive word on the question, if we only keep in mind how, just a few lines before speaking of the Capra Amaltea, he attributes entirely and solely to Pietro Bernini the Aeneas and Anchises, a piece of evidence that makes one conclude that [Sandrart’s] information about the Bernini Borghese statues could not have been obtained directly from Gian Lorenzo, who would have never acknowledged that statue as the exclusive work of his father. More generally, moreover, as all Sandrart scholars well know, in his Teutsche Academie, there is no lack of attributions that are patently unfounded, as for example, the attribution of the Arrotino [the ancient statue of the ‘Blade Sharpener,’ also known as the Scythian] to Michelangelo, nor are there lacking outright ‘falsifications,’ even regarding matters of which the German author had direct personal experience: suffice it to recall his controversial reconstruction of the famous painting exhibition held at the church of Santa Maria di Costantinopoli in 1632.”

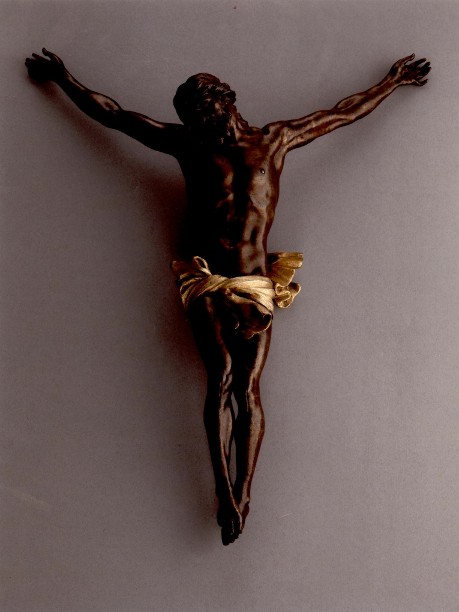

#73. The opinion of the former director of the Galleria Borghese on the bronze crucifix attributed to Bernini in the Art Gallery of Ontario

(for earlier discussions of this work, see below updates #50, #43, and #8; also #59 for a similar large bronze crucifix)

The monumentally comprehensive Bernini exhibition of 2017 at the Galleria Borghese placed so many of his sculpted works side by side for close comparative visual analysis, including two large bronze crucifixes, that from the Escorial in Spain (of secure, well-documented attribution) and the one attributed to Bernini that is now in the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto, a much debated attribution. One of the organizers of that landmark exhibit, Anna Coliva, former director of the Borghese and co-editor of the new “catalogo generale” of the gallery (Officina Libraria, 2022) summarizes the conclusion that she and many other scholars reached about the AGO work in a recent article (July 2023) in the online art journal, aboutartonline.com. Here is the passage in question:

“The placement of the marvelous gilded bronze crucifix from the Escorial, executed by Bernini between 1654 and ’56, next to the bronze crucifix acquired by the Toronto museum in 2006, revealed that a direct execution by Bernini [in the latter] was untenable, proposed first by Montanari on the basis of documentation deemed plausible but later refuted by new archival research (López Conde, 2011). In the [2017 Borghese] exhibition catalogue, completed before the works were displayed side by side, the attribution of the lending Museum [AGO] was duly respected. However, the many doubts and conclusions resulting from Scribner’s research (2017) were reported in detail and in concurrence. But it was the possibility of a comparative study offered by the juxtaposition of the two works that convinced us of the weakness of the attribution [of the AGO to Bernini]. The details, observable so close together, revealed the relative lack of skill in the casting technique of the Toronto version compared to the very high level of the one in the Escorial; just as the compactness of the proportions of the latter [Escorial] reveals the incongruous attenuation of the limbs which gives the Canadian Crucifix a ‘slithery’ shape. (trans. C. Scribner; emphasis added)

A recently published in-depth, clear, and thorough consideration of the question of the attribution of the AGO corpus by Jonathan Salem-Wiseman, professor of philosophy of Toronto, Canada: “But Is It a Bernini? A Tale of Contested Identity in the Art World.”

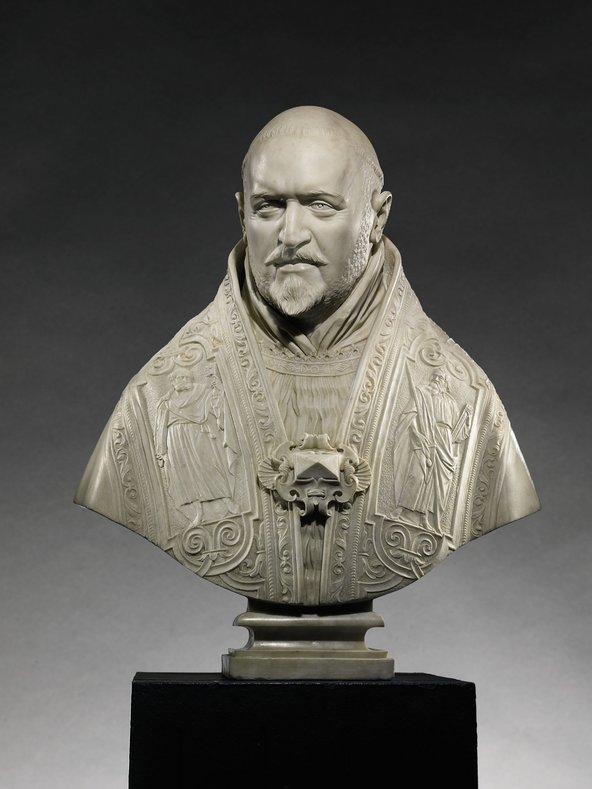

#72. The “Antonio Coppola” bust is definitely by Pietro Bernini, and only Pietro

One of the results of the monumentally comprehensive Bernini exhibit of 2017 at the Galleria Borghese — which placed so many of his sculpted works side by side for close comparative visual analysis — was to confirm the attribution to Pietro Bernini of the marble portrait bust of Antonio Coppola, which had already been given to Pietro by Hans-Ulrich Kessler in his 2005 catalogue raisonné of Pietro (see my Domenico note, p. 280, n. 13). Former director of the Borghese and co-editor of the new “catalogo generale” of the gallery (Officina Libraria, 2022) discusses this in a recent article (July 2023) in the online art journal, aboutartonline.com

In the same article, discussing other results of the 2017 close juxtaposition of Bernini works, she deconstructs (persuasively) the attribution of the Capra Amaltea (The Goat Amalthea) to Bernini (see my Domenico note, p. 279, n. 13 and Update #10 below), as well as the much debated bronze corpus of the crucified Jesus in the Art Gallery of Ontario.

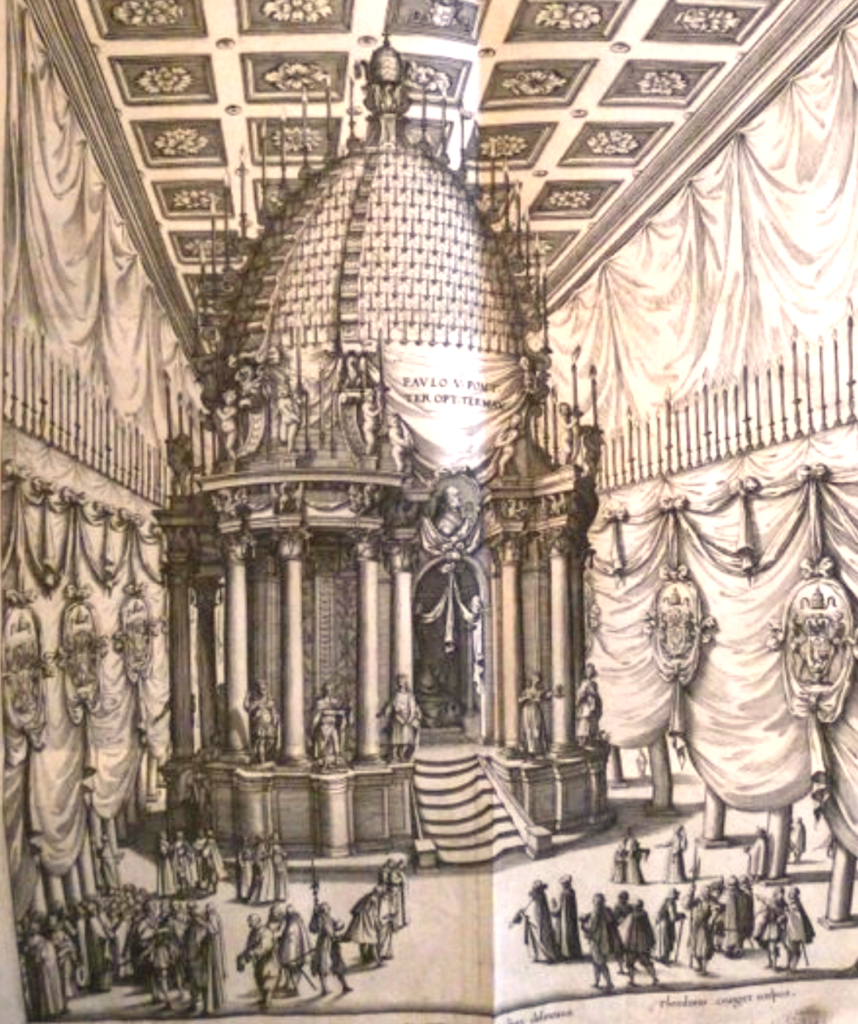

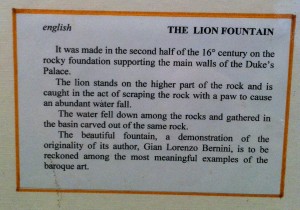

#71. Bernini’s Sculptures for the 1622 Pope Paul V Catafalque

I have only now come across the 2013 Columbia University doctoral dissertation by Arianna L. Packard, “The Catafalque of Paul V: Architecture, Sculpture, and Iconography.” It is the first, in-depth research into the early papal commission which involved Bernini. The principal architects of the project were Sergio Venturi and Giovanni Battista Soria, with Bernini supplying designs for the 36 allegorical sculptures, which he also executed with the help of assistants. Since the sculptures were an intimate part of the architectural structure of the catafalque, perhaps Bernini had some ideas to contribute to the overall design but the latter cannot in any way be attributed to him. The contemporary source for this monumental memorial to Pope Paul is Lelio Guidiccioni’s Breve racconto della trasportatione del corpo di Papa Paolo V…. (Rome, 1623), whose copious detailed information is confirmed and augmented by Packard’s own original research (see especially pp. 148-57 of the dissertation).

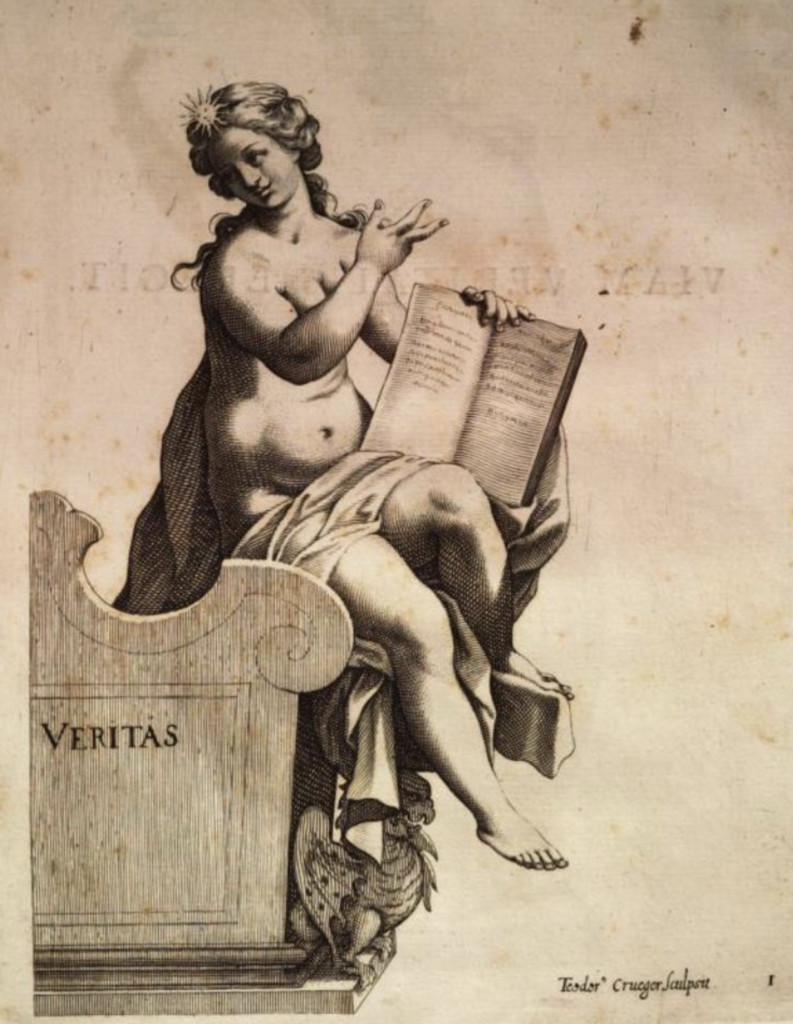

The engravings of Bernini’s statues were done by Dietrich Krüger (German, 1575-1624) upon drawings by Giovanni Lanfranco, of which is reproduced below that of “Veritas,” taken from the Breve racconto.

Bernini, Allegory of Truth for the Pope Paul V Catafalque of 1622, from Guidiccioni’s “Breve racconto”

#70. Bernini’s Sant’Andrea al Quirinale: A succinct, insightful new appreciation

Just published: Charles Scribner, “Bernini’s Stage for a Sacred Opera,” Sacred Architecture, issue 41, 2022, pp. 25-28: Scribner Sant Andrea al Quirinale 2022.pdf

#69. Bernini’s Bust of the Medusa: Additional Bibliography

In note 11, p. 319 of my Domenico edition, I briefly discuss a work not mentioned by Domenico but attributed to Bernini by virtually all Bernini scholars since Stanislao Fraschetti (in 1900), the magnificent bust of the Medusa. To the bibliography given in my note, please add Steven F. Ostrow’s careful, insightful analysis of the utter originality and meaning of Bernini’s representation of Medusa in his new article, “Bernini and the Poetics of Sculpture: The Capitoline Medusa” (in Arion 29.1, Spring-Summner 2021, pp. 1-17: Ostrow, Bernini and the Capitoline Medusa).

As Ostrow points out (p. 7): “In carving his Medusa, Bernini departed radically from [the long] visual tradition [of depicting Medusa] in a number of significant ways,” which are explicated in the remainder of the article. One noteworthy departure I will here mention is the fact that Bernini does not depict her at the time of her decapitation but rather earlier in her life when she, a beautiful woman with beautiful hair, is punished by Minerva for the desecration of her temple, as recounted by Ovid’s Metamorphoses (4:787-803) which turned her into a repugnant, malignant monster. Hence, the sorrow we see so poignantly sculpted in her face.

As both Ostrow (p. 12) and Lavin (in the 2007 article cited in the aforementioned note to my Domenico edition) point out, Medusa, a popular subject in art, classical and early modern, is featured in the bestselling Renaissance mythologies, Vincenzo Cartari’s Vere e nove imagini and Natale Conti’s Mythologiae. As Lavin (but not Ostrow) specifies (2007, p. 125), in these Christian moralized accounts of classical mythology (as elsewhere), Medusa became the icon of the carnal lust, of the evil woman who lures men into sin with her beauty.

HOWEVER, even though the point may not be necessarily relevant to the meaning of Bernini’s bust, I simply cannot help but point out that this demonization of Medusa in the Christian tradition is an example of “blaming and punishing the victim:” according to the source, Ovid, Medusa was the victim of rape by Neptune who was inflamed by her beauty; there is absolutely nothing in Ovid’s text to suggest that Medusa had lured him into committing the sacrilege of “ravishing” her in Minerva’s temple. Neptune was the perpetrator of the crime, yet he apparently got off “scot free.”

#68. A Bernini “Cristo Vivo” Crucifix in the Princeton Art Museum

Yet another important Bernini work in the Princeton University Art Museum is one of his autograph “Cristo Vivo” crucifixes. Charles Scribner has just published a thorough, well-documented article on it in the Princeton University Art Museum Record, 2021, vol. 77-78: pp. 14-23 (for pdf: Scribner 2021 Cristo vivo) which should be required reading for anyone studying any of the Bernini crucifixes of any size. The whole larger issue of the various Bernini crucifixes is a very complicated one: for further information, see below, updates ##8, 43, 50A & B, and 59.

#67. An important Bernini drawing in the Princeton Art Museum

One of the last essays written by the late Irving Lavin was “Bernini and the Figura Serpentinata: A Drawing Given to the Princeton Art Museum by Charles Scribner III in Honor of Professor Irving Lavin” (Princeton University Art Museum Record, 2021, vol. 77-78: pp. 14-23; for pdf: Lavin 2021 PUAM_Record_vol 77-78.) It presents his reflections on a drawing for a tomb monument that I discovered in a private collection in New England, which, as I argue in my article in Burlington (159 [Nov. 2017]: 886-92), was most likely Bernini’s design for a tomb monument for Tommaso Rospigliosi, the nephew of Pope Clement IX.

#66. The “paragone” (competition) between painting and sculpture

Domenico Bernini (Chap. 5, orig. pp. 29-30) quotes his father’s opinions regarding “the difference between painting and sculpture” and in doing so, evokes the long-standing issue of the “paragone” between the two arts, even though the term is never used here. I have only now become aware of an excellent, exhaustive monograph on the topic, which I recommend to you: Sefy Hendler, La guerre des arts. Le paragone peinture-sculpture en Italie XVe-XVIIe siècle (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2013), with many illuminating pages on Bernini. Here is an excerpt downloaded from academia.edu: La_Guerre_Des_Arts (Table of Contents, Preface and first pages of the Introduction).

#65. The painting of Christ bequeathed by Bernini to Pope Innocent XI (Chap. 23)

I would like to add a few more details to my limited discussion (in my notes 20-21 on p.421) of the painting of Christ the Savior that, according to Domenico (Chap. 23 orig. p. 176), Bernini bequeathed to Pope Innocent XI Odescalchi. The painting, says Domenico, was by the hand of his disciple Gaulli, whereas Baldinucci, in reporting the same bequest, says it was by Bernini himself. Although there have been scholars who have had no problem with Domenico’s assertion, I agree with Francesco Petrucci who finds it highly improbable — saying so in his various discussions of the painting — that Bernini would have given to the pope a gift of less exalted status, i.e., a painting by a young disciple, rather than one from his own hand. But more importantly, 2 contemporary avvisi di Roma in publicizing the gift specify that it was by Bernini himself. Indeed, a painting of Christ the Savior explicitly attributed to Bernini is found in more than one inventory of the Odescalchi family whereas no work by Gaulli is mentioned.

Petrucci discusses the issue in at least 3 of his works: “Bernini, Algardi, Cortona ed altri artisti nel diario di Fabio Chigi Cardinale (1652-1655), Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale d’Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte, 53 (III serie, XXI), 169-196, here 193-194; “L’opera pittorica di Gian Lorenzo Bernini,” in Bernini a Montecitorio. Ciclo di conferenze nel quarto centenario della nascita di Gian Lorenzo Bernini, ed. Maria Grazia Bernardini (Roma: Camera dei deputati, 2001), pp. 59-91, here 79-80; and, most recently and most extensively, in his exhaustive catalogue raisonné, Bernini pittore (Roma: Bozzi, 2006), in which he argues persuasively for the identity of the painting with a work in a British private collection: see p. 355, cat. entry 39 (under “opere autentiche”) as well as the relevant pages in the long introductory essay to the volume; for the painting, see the photo above.)

A doctor at work. Cornelis de Bie (1621-64)

#64. Which papal physician visited Bernini during his illness? (Domenico, Ch. 7)

As my note to this episode (p. 318, n. 5) mentions, the extant sources are confusing as to which doctors normally attended to the health needs of Pope Urban VIII and therefore which one of them was sent to attend to Bernini during his grave illness of ca. 1635. Domenico leaves the impression that the pope only had one, but in fact there seem to have been more than one serving at any given moment. To the names mentioned in my note must be added that of Dr. Sebastiano Vannini (who in fact is listed in the Marini book cited in the note).

Vannini (of Siena, as his family name proclaims) was the young protegé of Urban’s famous personal physician, Giulio Mancini, and like Mancini — and because of Mancini — was very interested as well in the fine arts. Arriving in Rome in 1618, Vannini immediately began his studies with Mancini and eventually succeeded to the post of papal physician upon the 1630 death of Mancini. He remained the (or an) “archiatra pontificio” throughout the rest of Urban’s reign. Extant are Latin poems by Vannini in praise of several of Bernini’s works created for Pope Urban, discussed by Fabrizio Federici, in “‘Bernini artificis prodigiosa manus.’ Il mecenatismo di Urbano VIII nelle rime latine di Sebastiano Vannini,” Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenshaft, 44 (2017): 63-84.

Bernini (attrib.), Marble skull for Pope Alexander VII, 1655-56 (Schloss Pillnitz, Dresden; image: The Art Newspaper)

#63. Rediscovery of the skull commissioned by Pope Alexander VII

It is well documented that very early in his pontificate, Pope Alexander VII ordered a coffin and a skull from Bernini to keep as “memento mori” in his private quarters (see my Domenico edition, p. 404, n. 22 for bibliography). We see the skull in a painting (below) by Bernini’s workshop painter-assistant, Guido Ubaldo Abbatini, dated 1655-56, now in the collection of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta in Rome. The coffin and the skull disappeared centuries ago from sight. Maybe the pope was buried in the coffin? In any case, the skull has just been re-discovered in Dresden. (Among other sources of this news, see the Smithsonian Magazine article on it, or The Art Newspaper article dated May 28, 2021 by Catherine Hickley.) The skull had been purchased in 1728 from the Chigi family along with other works of art (antique sculptures above all) by Augustus the Strong Elector of Saxony (also King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania), through his chief art buyer, Raymond Le Plat.

The expertly executed skull — of fine white Carrara marble and long displayed at the Schloss Pillnitz, a palace south of Dresden — now figures prominently in an exhibition (placing it in its historical and cultural context) at the Semperbau in Dresden entitled Bernini, the Pope and Death (May 28-September 5, 2021).

But did Bernini really sculpt the skull himself?

No. The attribution should really say: “Bernini and workshop.” Even in the earliest years of the reign of Alexander VII, Bernini would never have had the time or necessity to sculpt a mere skull of his own hand, or mostly of his own hand, nor would Pope Alexander ever have expected him to do so — just as he would not have expected Bernini to make the lead-and-wooden coffin that he commissioned from Bernini at the same time: Bernini was no carpenter and no metal worker. What he was for Pope Alexander (in addition to being a sculptor, architect and urban planner), was what we would today call a “general contractor” — i.e., the pope would routinely commission smaller items from Bernini, knowing that the artist would then contract them out to other, competent experts who did most of the work, whose quality of course was guaranteed by Bernini.

Yes, the skull is indeed finely made and of high quality marble, but skulls were so omnipresent in the art of Baroque Rome, that any self-respecting ambitious sculptor would know how to produce a good, convincing skull: they are not difficult to do! Hence, I suspect most of the work of the skull, except perhaps for finishing touches, was done by a Bernini assistant, with Bernini, of course, watching over him every so often.

The Dresden curator, Dr. Claudia Kryza-Gersch, is quoted as saying in the aforementioned Art Newspaper article, “Three days after Alexander VII was appointed Pope in 1655, he commissioned a sarcophagus [sic! it was, instead, a coffin] and the death head from Bernini. That makes it unlikely that the sculpture was by Bernini’s workshop…. The preceding years had been troubled ones for the sculptor, then in his late 50s, and he had fallen out of favour. He had to grab the opportunity and make it work…. If you get a commission from the new pope in that situation, you do it quickly and you do it yourself.”

With all due respect to German curator, I must point out that by 1655 Bernini was by no means in any dire or needy professional situation that he had to jump at the chance to execute this skull in order to gain the good graces of the new pope: it is well known that Pope Alexander was in fact very favorable towards Bernini from the very start of his pontificate. Indeed, even before becoming pope, Alexander commissioned Bernini (in 1650) to complete the family chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo (while later, once Alexander became pope, he had the artist renovate the entire church, both its interior and exterior). In 1655 Alexander even named Bernini “Architetto della Camera Apostolica.”

After the superlative successes of the Cappella Cornaro (with its Ecstasy of Saint Teresa) and the Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona (which regained him the favor of Pope Innocent X), Bernini had several years prior already re-acquired his glory and professional security (temporarily lost after the ignominious failure of the bell towers he erected for St. Peter’s). Moreover, in the 1650s, Bernini was extremely busy with other, greater commissions: these include portraits of the pope (in various media), design of the Cardinal Pimental tomb (in the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva), preparations for Queen Christina of Sweden’s grand entrance into Rome (which included the re-doing of the Porta del Popolo, designing a gift coach for her, and preparing the Torre dei Venti for her temporary residence), etc. — not to mention that he was probably already beginning the earliest conceptual preparations for the monumental works of the Colonnade of St. Peter’s, the Cathedra Petri, the Scala Santa, and various “Alexandrine” churches that Pope Alexander seems to have had in mind from the first days of his pontificate. Moreover, even though he escaped the bubonic plague pandemic that struck Rome in 1656, Bernini was nonetheless very sick intermittently from September 1655 to April 1656 with “febbri terzane doppie” (presumably a form of malaria), so much so that he even left Rome for the sea-side locality of Palo hoping to regain his health.

Guido Ubaldo Abbatini, Portrait of Pope Alexander VII at His Desk, 1655-56 (Sovereign Military Order of Malta, Rome; image: The Art Newspaper)

#62. More on the reception of Bernini’s Louis XIV Equestrian and the continuing efforts of Bernini’s sons to receive their French pensions

Most of the oft-cited contemporary documentation to the Parisian reception of Bernini’s Louis XIV Equestrian come from French sources, but one notable source is Italian, the letters of Angelo Maria Ranuzzi (1626-89), the “Nunzio Apostolico” (i.e. papal ambassador) to the French court, writing to Cardinal Alderano Cibo (aka Cybo, Secretary of State to Pope Innocent XI) in Rome.

Those letters, together with one of Ranuzzi’s assistant, Giovanni Battista Lauri, confirm what we hear in the French sources, namely, “La statua equestre ultimamente trasportata qua ha totalmente incontrata l’universale disapprovazione.” (The equestrian statue recently shipped here has completely met with universal disapproval.) [Source: Bruno, Neveu, ed., Correspondance du nonce en France Angelo Ranuzzi (1683-1689). Tomo I: 1683-1686. Rome: Ecole française de Rome / Università Pontificia Gregoriana, 1973, p. 637, excerpt from Ranuzzi letter 1692, dated December 17, 1685; for Lauri’s letter, see p. 638, letter 1697, bearing the same date, in the same volume; for discussion and English translation of the latter, see Robert W. Berger, In the Garden of the Sun King: Studies on the Park of Versailles under Louis XIV ((Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1985). p. 57.]

Let us note: The statue, as we know, had arrived in Paris several months earlier (i.e., March), so why is it still being discussed in December? Answer: because Msgr. Pietro Bernini had pressed the papal Secretary of State Cibo to use his influence to get Louis XIV to pay to Gian Lorenzo’s heirs the pensions that he had promised years earlier to their father (op. cit., p. 629, letter 1666, dated Nov. 27, 1685). In the rest of his December 17th letter, Ranuzzi goes on to explain (and I paraphrase): “I assure you, this is certainly not the time to ask for the pension money for the Bernini brothers: the king despises the statue as does everyone else at his court!” Strange that by this late date, Msgr. Bernini knew nothing of the total failure of his father’s statue. In any event, we can be sure that Cardinal Cibo duly reported what Ranuzzi said back to Pietro Bernini and his brothers. Yet, as I mention in the commentary to my edition of Domenico Bernini’s biography of Gian Lorenzo, the statue is discussed with great enthusiasm, as if it had been a universally loved success, not failure.

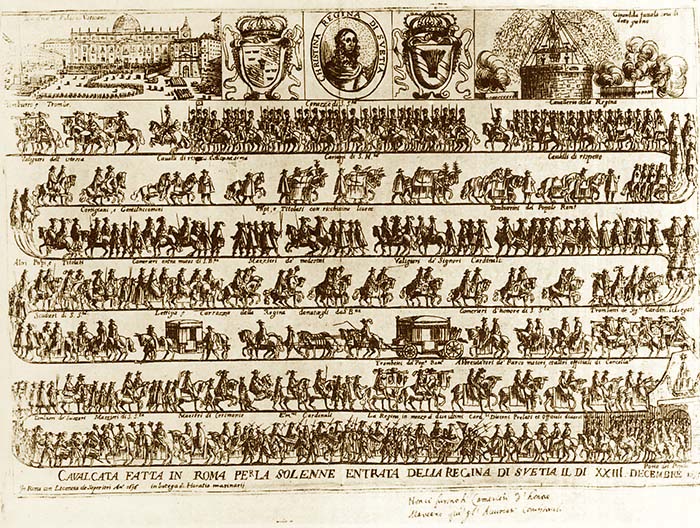

#61. Preparations for Christina of Sweden’s formal entrance into Rome (Domenico, Chapter 14, pp. 102-103)

An article of 2018 describes into greater detail (than D’Onofrio’s Roma val bene un’abiura of 1976) the many complicated and costly preparations — fraught with so many intricate, potentially troublesome questions of protocol — undertaken by Alexander VII and his masters of ceremonies to prepare for Christina’s entrata in late December 1655, culminating in a solemn ceremony in St. Peter’s on Christmas Day: Francesca De Caprio, “L’entrata in incognito di Cristina di Svezia in Vaticano: cerimoniali e simboli,” Settentrione (Nuova Serie): Rivista di studi italo-finlandesi 30 (2018): 187-211.

In order to combat the widespread cynical rumors that Christina had abdicated her throne and decided to move to Rome for anything but devout reasons, all of the papal many ceremonies in question were designed “to emphasize the spiritual, religious and penitential character of her journey [to Rome] from its very beginning” (De Caprio, 194).

So eager was Christina to arrive in Rome that Alexander had to send emissaries to Innsbruck to plead with her to slow down her journey so that all the proper preparations could be completed (De Caprio, 200-201), for, as Domenico says (p. 103), the pope intended “to receive her none otherwise than as if, the northern lands having been conquered, she were entering Rome triumphant.”

As did D’Onofrio, De Caprio (207-08) reproduces the description of the splendid coach designed by Bernini, given as a gift to the queen by Alexander, that comes to us from contemporary Galeazzo Gualdo Priorato, but unfortunately she adds no new details about either the coach or any of the interactions between Christina and Bernini.

#60. What exactly was Bernini’s role in the design of the Gesù cupola fresco done by his protegé Gaulli?

In his recently published article “Bernini, Baciccio and the Dome Fresco in the Gesu. A Reconsideration,” Steven Ostrow probes deeply into a long-debated question regarding the relative roles of the patron (Gian Paolo Oliva, S.J.), the artist (Bernini’s protegeé, G.B. Gaulli) and the behind-the-scenes artist-master (Gian Lorenzo Bernini) in the creation of the spectacular fresco adorning the cupola of the Jesuit mother church in Rome, the Gesù. As he summarizes (p. 289): “By carefully re-examining all of the relevant primary and secondary sources, and, more importantly, all of the visual evidence, my hope is to arrive at a more nuanced, and more accurate picture of what each of these three men contributed to the conception, design, and execution of the fresco.”

#59. Again on Bernini’s Crucifix formerly in the French Royal Collection.

Bernini, Crucifix for Pope Alexander VII, private collection, Germany; photo courtesy of Charles Scribner

My note 1 on p. 334 is in need of revision, in light of my re-reading of Montanari’s article, “Bernini Per Bernini: Il secondo ‘crocifisso’ monumentale. Con una digressione su Domenico Guidi,” Prospettiva 136 (2009): 2-25.

As Montanari therein states (pp. 6-8), the commission from Antonio Barberini for a crucifix and bronze bust of Urban VIII is first mentioned in Nov 11, 1655 letter to Bernini, written from Genoa when the cardinal was en route to Paris and again, very briefly, in his letter March 10, 1656 to Bernini. As Montanari observes, the commission in fact refers to objects intended for Antonio’s own home, not as gifts to Louis XIV (FM: which is probably why neither Domenico nor Baldinucci nor Chantelou ever mentions them). They were only donated to Louis when Antonio died in Nemi in August 1671 without a last will and testament, a donation made by his relatives. The two bronzes show up in the royal inventory by May 28, 1672.

From Charles Scribner (personal communication): The crucifix “is listed in the 1775 royal inventory but not in the 1788, or the 1791. Its subsequent whereabouts (if indeed it survived the Revolution) remain unknown. See Les Bronzes de la Couronne, Louvre catalogue, Paris, 2004, 87. . . It seems likely that Bernini’s crucifix for Cardinal Antonio Barberini . . . was comparable to the one Bernini made for Pope Alexander VII (… now in a German private collection), rather than a monumental bronze representing an additional casting of the corpus for Philip IV, as Wittkower assumed and others have followed. Indeed, as Franco Mormando notes in litteris, such an identical recasting of Philip’s Escorial crucifix for Cardinal Antonio might have risked a diplomatic slight to the Spanish king.”

(Dr. Scribner, by the way, is the only Bernini scholar to have devoted as much study as he has of the complicated question of Bernini’s bronze crucifixes, of all sizes and destinations. For more on the subject, see his article on the one in the collection of the Princeton University Art Museum.)

#58. Bernini’s Praise for the Pasquino statue:

Regarding the ancient, mutilated statue of the Pasquino, Domenico (13-14) claims that Bernini “was the first in Rome to accord a high place of esteem to this most noble statue.” In reality, as Donatella Livia Sparti points out, already in 1556 Ulisse Aldovrandi had published high words of praise for the work: “despite being broken and damaged, from what can be seen from its limbs and muscles it has been considered [by] the most excellent artists one of the most beautiful [sculptures] ever to be in Rome” (Sparti, “The ‘Rebirth’ of Ancient Sculpture in 17th-century Rome,” in Bernini, exh. cat., Galleria Borghese, eds. Andrea Bacchi and Anna Coliva [Milan: Officina Libraria, 2017], pp.75-83, here p. 76, quoting Aldovrandi’s “Delle statue antiche, che per tutta Roma, in diversi luoghi, et case si veggono.”)

#57. Another Bernini Exhibition: “The Holy Name. The Art of the Gesù: Bernini and His Age,” February 2 – May 19, 2018, Fairfield University Art Museum, Connecticut.

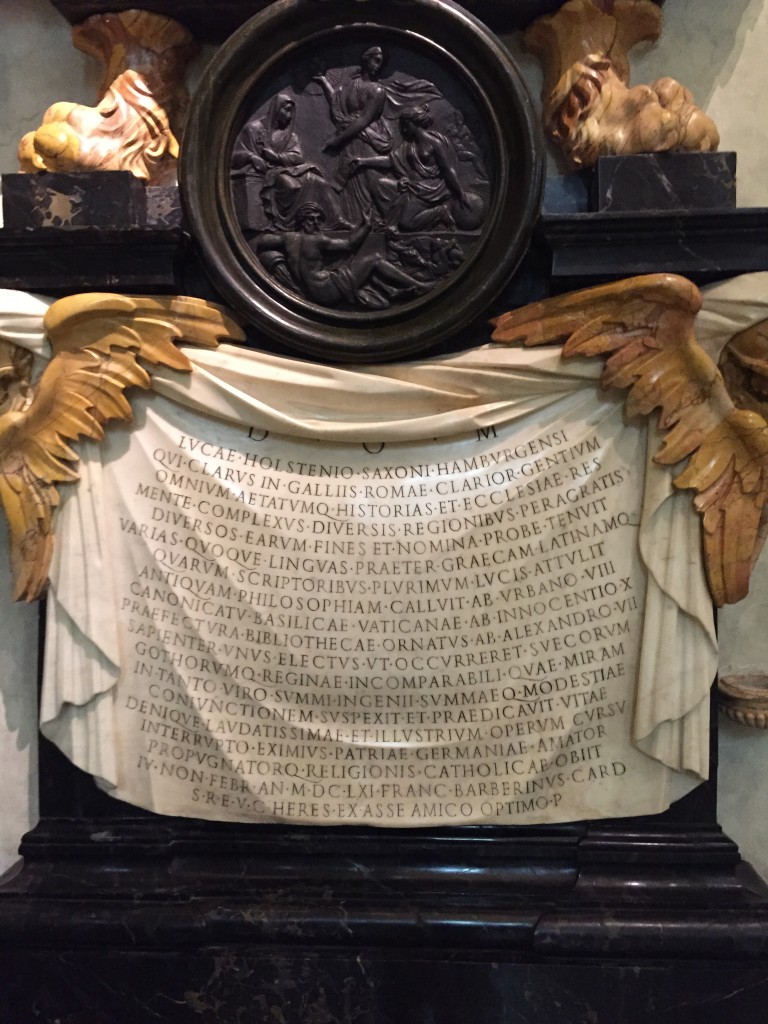

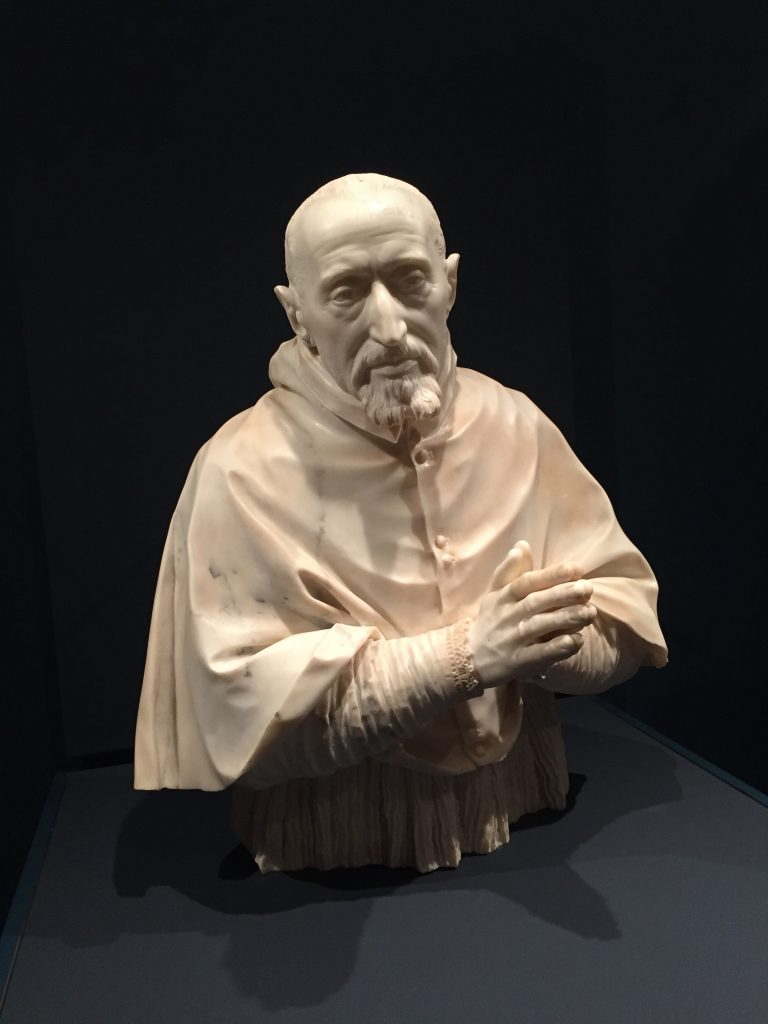

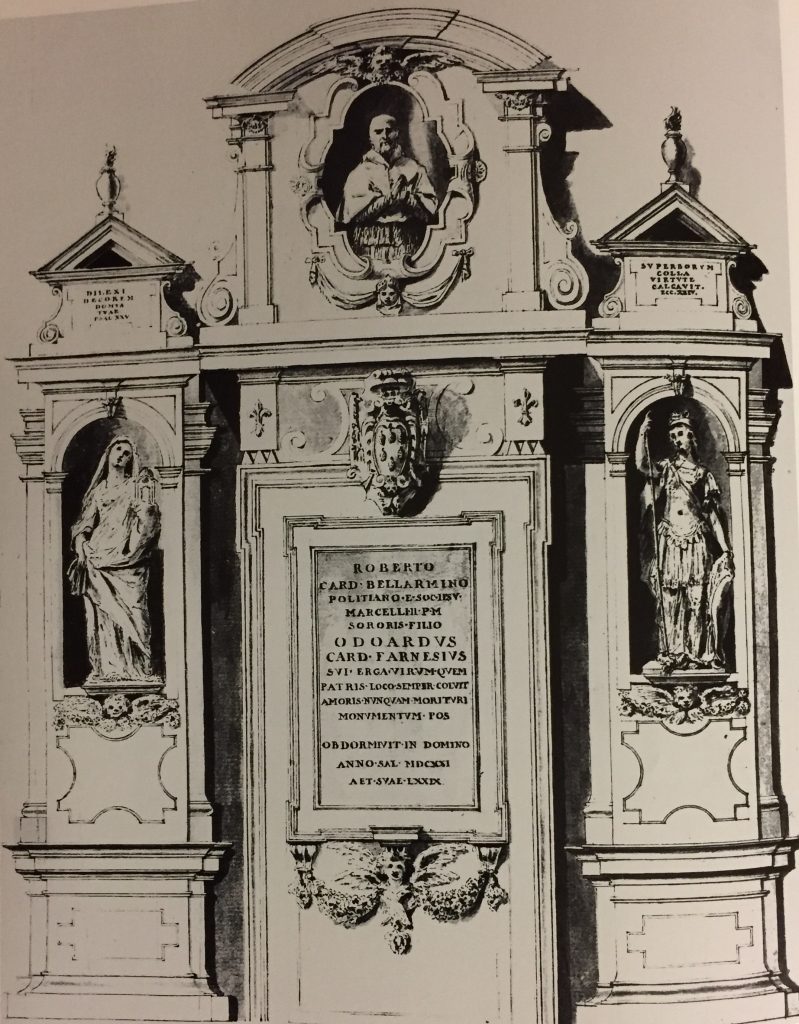

This landmark exhibit of sculpture, painting, drawings, engravings, decorative art and vestments (about 60 objects in all), focuses on the Jesuit mother church of the Gesù, Rome, and features the first appearance outside of Italy, of Bernini’s marble portrait bust of St. Roberto Bellarmino (1622-24, Domenico, p. 288, n. 49), newly restored for this exhibit. No longer can art historians ignore or belittle the quality and importance of this early portrait bust. Despite the saint’s placid pose (and the narrowness of the bust noticeable only when viewed from the side), it has that stirring psychological vivacity characteristic of all of Bernini’s portraits, even the earliest.

For the record: I was a member of the organizing committee and a contributor to the extensive catalog (entries plus several essays that are the fruit of original research), edited by Linda Wolk-Simon, director of the Fairfield University Art Museum. Included in the catalog is a major essay by Xavier Salomon on the Bellarmino tomb monument, which was disassembled in the 19th century, with only the Bernini bust remaining in the church (Solomon, in the course of his research, re-discovered the original inscription. Hopefully the two allegorical figures, have survived and are located in some Jesuit institution in Rome, their true identity unrecognized).

The Bellarmino tomb monument (sculpture by Pietro and Gian Lorenzo Bernini) in its original appearance.

#56. New Bernini exhibition: Galleria Borghese, Nov 2017-February 2018

This landmark exhibition gathers scores of works, from the world over, including private collections, and covering the entire span of Bernini’s life and production in multiple genres: sculpture, drawing, painting, clay models. The accompanying catalogue is now required reading for updated information and interpretations, including debated matters of chronology and attribution (most prominently the 2 busts of the Savior [Norfolk and San Sebastiano in Via Appia) and the two large bronze crucifixes [El Escorial and Toronto] ). Also introduced are a few newly discovered works, or putative works, including a painted portrait of Pope Clement IX (see note #38 below, newly updated).

Bernini’s Santa Bibiana, newly restored for the exhibit. In the course of the restoration, it was discovered that as it had been installed in its niche for many years, the statue had been mistakenly turned a few degrees toward the viewer’s right, which resulted, e.g., in the column acquiring too much visual prominence.

#56 bis. 2017 BERNINI EXHIBITION: CAT. IX.9: Bust of the Savior (Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia): by “Gian Lorenzo Bernini?”

The Galleria Borghese Bernini exhibit (catalogue edited by Andrea Bacchi and Anna Coliva) displays for the first time together, facing each other, two “Savior” busts purportedly by Bernini, that in Norfolk, Virginia (cat. IX.9) and the other in the church of San Sebastiano in Via Appia (cat. IX.10). Both entries are by the very expert Bernini connoisseur Francesco Petrucci, who places a question mark after the Norfolk bust Bernini attribution, noting (p. 328) that even the Chrysler Museum of Virginia that owns the bust attributes it only to “Follower of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.”

As I am not trained as a connoisseur, I usually refrain from making any pronouncements on matters of attribution. But having recently seen the exhibit and examined the two busts, I feel moved to put my two cents in… at least about the Norfolk bust.

Upon seeing the bust in Rome (and for the very first time), my spontaneous, uncensored reaction was: “Boy, is this ugly! It is too ugly to be by Bernini.” Not only inelegant and inexpertly executed but downright ugly.” Even those who defend the autograph status of the Norfolk bust — most notably Jennifer Montagu (as she firmly reiterated during the “Giornata di Studio” organized by the Galleria Borghese on Jan. 22, 2018) — admit it is unattractive. According to Montagu, who staunchly defends the Bernini attribution, the bust is a product of a “Bernini pazzo,” again as she claimed at the Borghese Gallery in January 2018, and as she has said in print.

I reject it as by Bernini or even his workshop. My reasoning is based on common sense and historical facts:

1. All sources indicate that Bernini was in full possession of his mental acuity until the very end of his life, even after his stroke. He was not demented one bit. Indeed, at the age of 79 Bernini received yet another papal commission, that of restoring the venerable Palazzo della Cancelleria, a great confirmation of his undiminished powers. As for the Savior bust, both of Bernini’s early biographers, Filippo Baldinucci and Domenico Bernini, states that Bernini had high regard for this work of his, considering it his “beniamino” (“most beloved child,” as Baldinucci reports).

2. Having nothing wrong with his mind or his eyes, if this bust were by him, he would have been perfectly aware that it fell far below his life-long standard of excellence. He would not have allowed himself to be in a state of denial. And he probably would have noticed the poor quality of execution well before bringing the bust to completion: in fact, once he had noticed that decay in quality, he would have stopped work on it mid-way, rather than bringing it to completion. Why in the world would he want to immortalize forever the decline of his magnificent skills in the form of this marble bust, for all the world to see and say, with pity or satisfaction: “See what the great Bernini has been reduced to?!”

3. Moreover, seeing the poor quality of his work (if it were indeed his work), he would never have dreamed of insulting Christina of Sweden — a friend, a protectress, and a monarch — by making a gift to her of so grossly inferior a work (and we do know for certain that the Savior bust was bequeathed by Bernini to Christina.) Baldinucci tells us that while in visit to Queen Christina in Rome, she showed him the Savior bust with great pride and ceremony.

4. If, seeing that he could not execute the bust properly and deciding to give it to one of his assistants to either finish or “fix up,” Bernini would have chosen someone of far greater talent than whoever it was who did the Norfolk bust. There were many sculptors of extraordinary talent surrounding Bernini, even if they did not reach public fame. He did not have to rely on someone of such mediocre skill.

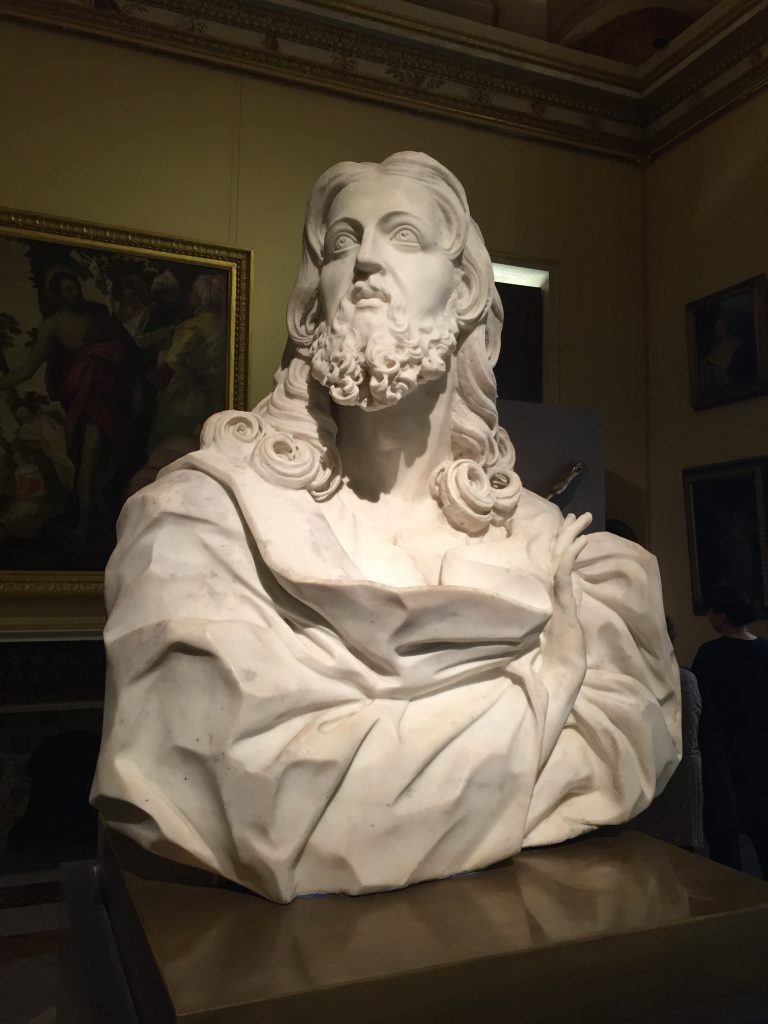

#55. Sculptors from Carrara in the Bernini workshop: Francesco Baratta, Andrea Bolgi, Giuliano Finelli, & Domenico Guidi

For further information on these men, see the copiously illustrated book, I Carraresi a Roma: Le opere degli scultori dal ‘600 ai giorni nostri by Giancarlo Beneo (Carrara: Comune di Carrara & Rotary Carrara e Massa, 2015). And now in English: The Carraresi in Rome: Marble and Bronze Works Sculpted in Rome by Sculptors from Carrara (from sixteenth century to our days (Pontedera: Bandecchi & Vivaldi, 2019):

#54. Ercole Ferrata and Giuliano Finelli: Bibliography

Ercole Ferrata, statue of papal nephew Tommaso Rospigliosi, 1669, Sala dei Capitani, Musei Capitolini, Rome (photo: Beverly Joel, courtesy of Jessica Boehman)

For the most thorough and most recent study of major Bernini collaborator, the sculptor Ercole Ferrata, see Jessica M. Boehman, “Maestro Ercole Ferrata” (Ph.D. thesis), Dept. of the History of Art, University of Pennsylvania, 2009.

For a most thorough study and catalog raisonné of another major Bernini collaborator, the sculptor Giuliano Finelli, see Damian Dombrowski, Giuliano Finelli: Bildhauer zwischen Neapel und Rome (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1997).

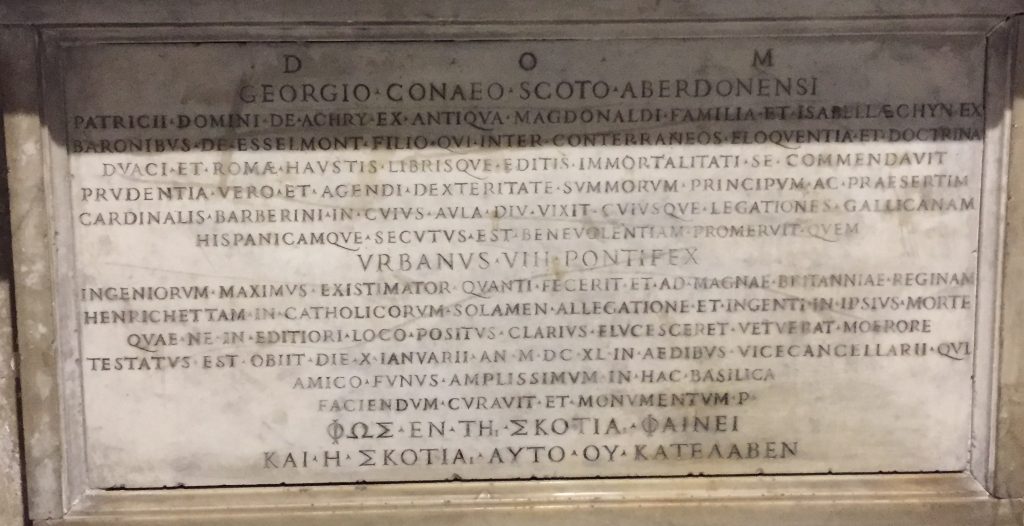

#53. George Conn, papal agent in London and Barberini favorite (Domenico, 336 n. 13):

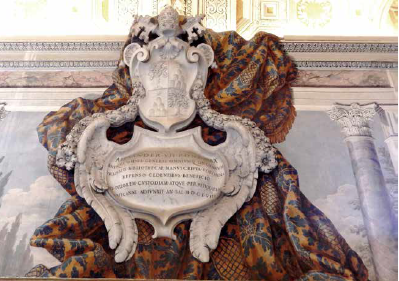

As mentioned in my note, Conn died young in Rome in 1640; a funerary monument is in the basilica of San Lorenzo in Damaso, Rome, which a small plaque next to it attributes to the “scuola berniniana;” the portrait of Conn and the cherub holding it aloft were in fact done by Lorenzo Ottoni, with Giuseppe Giorgetti contributing to the remainder of the monument (for bibliography, see Oreste Ferrari and Serenita Papaldo, Le sculture del Seicento a Roma [Rome: Bozzi, 1999], p.182) The sources speak of his “masculine charm” which the effigy seems not to convey.

Tomb of George Conn, San Lorenzo in Damaso, Rome (photo: F. Mormando)

Bernini & GP Schor, Wall decoration, Galleria di Urbano VIII, Vatican Library

#52. Smaller Works by Bernini during the Chigi Pontificate (Domenico, orig. pp. 107-8)

In his article, “Giovanni Paolo Schor pittore: tra Pietro da Cortona e Bernini” (Valori tattili, 7, 2016, 101-17), Francesco Petrucci brings to light a new work of Bernini’s design (p. 104): a wall decoration (in marble and fresco) in the Galleria di Urbano VIII of the Vatican Library featuring the papal coat of arms and an inscription in honor of Alexander VII. The source for this commission is the until-now overlooked entry in Alexander’s diary dated October 22, 1662.

#51A. The anti-Bernini pamphlet, Costantino messo alla berlina (Domenico, 256n.71 & 365n.18)

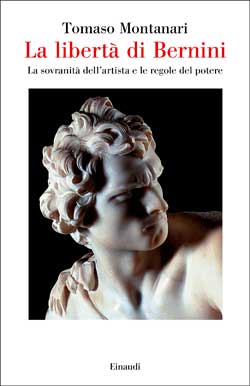

Tomaso Montanari publishes the complete text for the first time in appendix to his La libertà di Bernini: La sovranità dell’artista e le regole del potere (Turin: Einaudi, 2016), 304-318 (with his intro and notes). Note that according to Montanari, the pamphlet dates to 1670, not to 1725 as argued by earlier scholars.

#51B. Regarding Montanari’s same 2016 book, we have this cogent global assessment from Evonne Levy in her illuminating essay, “Wittkower’s Old Oak Branches: Thirty Years of Bernini Studies (1980s-today)” in the 2017 Bernini (Galleria Borghese) exhibition catalogue (eds. A. Bacchi and A. Coliva, pp. 357-67)

“The book that goes the farthest in deconstructing the Bernini of the [earliest official apologetic] biographies [by Baldinucci and Domenico Bernini] is Tomaso Montanari’s La libertà di Bernini….. With the stated goal of dismantling Giuliano Briganti’s characterization of Bernini as the reactionary antithesis of the revolutionary Caravaggio, Montanari asks us to look behind Bernini in the guise of the successful courtier, a conservative artist — an image Bernini himself helped to craft and which, in the modern Italian historiography, aligned him with the Italian Democristiani [FM: i.e., the right-wing political party, aligned with papal interests that long ruled Italy from 1948ff]. In recasting Bernini, Montanari, supported by the anti-hagiographic biography of the artist by Franco Mormando (2011), dug into the anti-Berninian literature. He exposed the extent to which the biographies suppressed Bernini’s conflicts with his patrons, and the outright failures and avowed limitations in painting and architecture that contradict the biographers’ image of Bernini as a universal artist cast in Michelangelo’s image. Montanari interestingly draws Bernini close to Caravaggio… [specific and persuasive parallelisms follow]….” (Levy, 366)

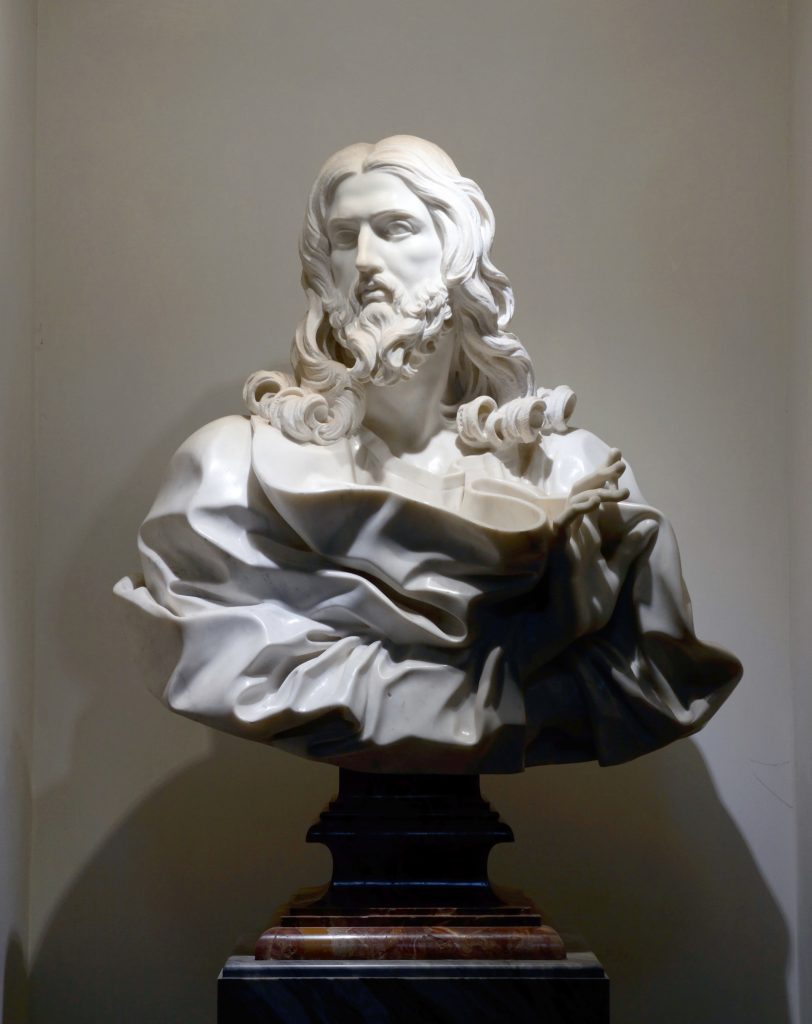

Bernini, Bust of the Savior, San Sebastiano fuori le mura, Rome (photo: Charles Scribner III)

#50A. Bernini’s bronze life-sized Crucifixes and his Bust of the Savior

See Charles Scribner III’s newly published “Imago Christi: Bernini’s Saviors, Lost and Found” for a carefully argued, extremely nuanced, and insightful discussion of Bernini’s life-size crucifixes (including that for King Philip IV and the Toronto bronze crucifix attributed to Bernini) and his Bust of the Savior (San Sebastiano, Rome), covering matters of textual documentation, iconography, and the neuralgic point of connoisseurship. There are few people who have looked as carefully at Bernini’s works as Scribner, and who can therefore speak as authoritatively about vexed, complicated matters of attribution.

See also the entries (VIII.10 and VIII.11, pp. 284-288) both by Maria Giulia Barberini (with ample bibliography) dedicated to the two bronze crucifixes — that of the Escorial and that in Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto — in the catalogue of the 2017 Bernini exhibition at the Galleria Borghese. Also important to any discussion of these crucifixes is the entry by Francesco Petrucci (cat. 20, pp. 88-101) in the exhibition catalogue, La Passione di Cristo secondo Bernini: Dipinti e Sculture del Barocco Romano (Roma: Bozzi, 2007).

#50B. THE QUESTION OF THE LARGE BRONZE CRUCIFIXES IS VERY COMPLICATED! to wit…

We know of the following large crucifixes connected to Bernini all dating from 1664ff:

1. The one in the Escorial (well-documented and attribution universally accepted);

2. The one formerly in the Royal Collections, Paris — probably donated to King Louis XIV by Cardinal Antonio Barberini — duly described (with measurements) in the royal inventories from which it disappears, however, sometime between the compiling of the 1722 inventory and that of 1788 which lists it not (nor is it listed in that of 1791).

3. The one in a private collection in Germany, “perhaps coming from the Chigi collection” (Petrucci 2007), but which cannot be identified with the one formerly in the French royal collection because it is smaller in dimension. This German crucifix could be the autograph second version of the Escorial crucifix made by Bernini upon request from Pope Alexander VII Chigi, as noted in the papal diary on October 1, 1656 (Petrucci, 2007, 101; the diary entry speaks of a desire for such a replica, a desire which Bernini is not likely to have ignored).

4. The one currently in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, the attribution of which is highly debated. Is it a later pastiche (as Charles Scribner holds)?

5. The one whose precise measurements are unknown but which is described as being “large” and “similar” — in design but not exactly in size? — to that of the Escorial given by Bernini to Jesuit Cardinal Sforza Pallavicino. For the longest time and until 2011 when Lopez Conde published his new documentation (for which see update #43 below), it was taken for granted that Bernini indeed had given Pallavicino this replica in bronze, but now we know, thanks to Lopez Conde, that the Bernini gift crucifix was made of polychromed papier-mâché. (See my note #43 below as to why I never thought that Bernini would have given Pallavicino a crucifix not only made of extremely expensive bronze but also equal in size to that belonging to the King of Spain ). In any event, Pallavicino in turn, at his death (1667), bequeathed his Bernini gift crucifix to Roman scholar-poet (and member of court of Christina of Sweden), Stefano Pignatelli (d. 1686, not to be confused with Scipione Borghese’s notorious lover and cardinal of the same name [1578-1623]). At his death, Pallavicino gave yet another Bernini crucifix to his friend, Theatine Father Carlo de’ Tomasi, this one described as a polychromed “modello” (again, see update #43 below).

#49. A new addition to the portraiture by the young Bernini (Domenico, orig. pp. 9-10 and Pietro Filippo Bernini, Vita Brevis di GLB, Appendix 1, p. 239)

Cenotaph of Giovanni Angelo Frumenti, Baptistry, Santa Maria Maggiore, with portrait bust attributed by Steven F. Ostrow to Gian Lorenzo Bernini, ca. 1615-17 (photo: Alessandro Vassari, in “Burlington” CLVII, July 2016, p. 521 (detail)

The July 2016 issue of Burlington (vol. CLVII, pp. 518-28) contains Steven F. Ostrow’s article, “Giovanni Angelo Frumenti and his tomb in S. Maria Maggiore: a proposed new work by Gian Lorenzo Bernini,” making a persuasive case for the attribution of a long-ignored portrait of a long-forgotten canon (d. 1621) of the basilica by the young Bernini (Ostrow dates it to ca. 1615-17). The portrait is incorporated within canon Frumenti’s cenotaph in the Baptistery of Santa Maria Maggiore and in that not-easily accessible location is easily overlooked, which would explain why it has taken so long for scholarly attention to be directed upon it. As Ostrow notes (p. 527): “The portrait of Frumenti is of such high quality that there can be little doubt that it is an autograph work by Bernini; there was no other sculptor active in Rome at the time capable of this kind of invention and carving.” As Ostrow (p. 528) also reports, the Bernini family and canon Frumenti knew each other very well.

#48. How large was the size of the block of marble used for Bernini’s Constantine? (Domenico, p. 366 n 19)

Marble Quarry at Carrara, Italy (photo: wikimedia)

In update #45 (below), I promised to address this question further. The answer is long and complicated, and may entail much more information than anyone really wants to know, but I have addressed it in this separate pdf: Carrettata Size and the Constantine statue

#47. Bernini’s explanation for the stability of the Four Rivers Fountain (Domenico, orig. p. 90)

#47. Bernini’s explanation for the stability of the Four Rivers Fountain (Domenico, orig. p. 90)

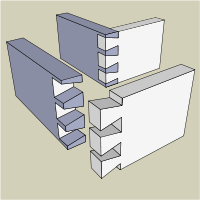

I realize that one line of my translation in this passage should be more literal and read thus:

“… all of the adjoining parts of the rocky mount being cut and joined in dovetail fashion, each piece is thus encased within the other, forming a most steadfast bond … “

As I mention at the end of my Introduction (p. 74), any scholar using Domenico’s text for the purposes of critical, close analysis or technical discussion, should, of course, always consult the original Italian text.

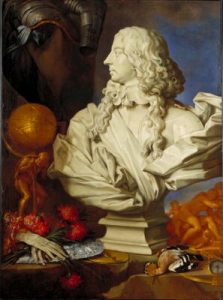

#46. Bernini’s bust of Francesco d’Este (Domenico, orig. p. 64)

Add to the bibliography in note 2 on pp. 334-35 Steven F. Ostrow’s article about the “after-life” of the portrait bust in the form of an allegorical painting created in Modena not long after the arrival of Bernini’s bust, which Ostrow (with sound reasoning) attributes to Modenese painter, Francesco Stringa: “(Re)presenting Francesco d’Este I: An Allegorical Still Life in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts,” Artibus et Historiae, v. 32, n. 63 (2011): 201-16. About the painting, Ostrow (p. 212) remarks: “What we have, in fact, is a portrait of a portrait, which wittily plays with the art of portraiture and the illusionistic powers of art.”

Add to the bibliography in note 2 on pp. 334-35 Steven F. Ostrow’s article about the “after-life” of the portrait bust in the form of an allegorical painting created in Modena not long after the arrival of Bernini’s bust, which Ostrow (with sound reasoning) attributes to Modenese painter, Francesco Stringa: “(Re)presenting Francesco d’Este I: An Allegorical Still Life in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts,” Artibus et Historiae, v. 32, n. 63 (2011): 201-16. About the painting, Ostrow (p. 212) remarks: “What we have, in fact, is a portrait of a portrait, which wittily plays with the art of portraiture and the illusionistic powers of art.”

Ostrow also mentions (p. 205) a fact that I neglected to include in my note: the “author of one of the portraits that was meant to serve Bernini as a model for the bust” was French painter, Jean (Giovanni) Boulanger of Troyes, “court painter to Francesco d’Este.”

#45. Giacomo Borzacchi, one of the unsung hero’s of Bernini’s Rome

Karen Lloyd’s article, “Capomastro and Courier: Giacomo Borzacchi and Bernini’s Equestrian Statue of Louis XIV in Transit,” (in Making and Moving Sculpture in Early Modern Italy, ed. Kelley Helmstutler Di Dio, Farnham: Ashgate, 2015:191-205) sheds new light on Borzacchi, a 30-year employee of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro and one of the unsung, behind-the-scene heros of Bernini’s Rome, the amazingly talented masons, craftsmen, and engineers (like Luigi Bernini) who performed feats of construction marvel for the “sung heros” like Bernini, Borromini, and Pietro da Cortona. It was Borzacchi who oversaw the actual assemblage of the near miraculous composition of Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona — a task which included putting back the broken pieces of the obelisk.

Lloyd’s article focuses on Borzacchi’s service to King Louis (and the Bernini family) in overseeing the packing and transporting of the Louis XIV Equestrian statue in 1685. Of special note in the article is the report (p. 197) of Minister Louvois’s rejection of Mattia de’ Rossi’s grandiose designs for an architectural setting for Bernini’s statue in Paris for they “were so expensive that they were of no use.” (Like master, like disciple!). There is a presentation drawing of Mattia’s setting design in the Fond Robert de Cotte in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

In a footnote (p. 199, n. 13), Lloyd has occasion to cite (without comment) Irving Lavin’s calculation of the prodigiously large single block of marble used by Bernini for his Constantine: Laving’s calculation may not be entirely correct, and is in need of commentary. Stay tuned for an update on this and on the larger question of how large was a carrata or carrettata of Carrara marble in Bernini’s time? (now see entry #48 above)

Bernini: Church of S. Tommaso da Villanova, Castel Gandolfo (foto: F. Mormando)

#44. Bernini’s Church of San Tommaso da Villanova, Castel Gandolfo (Domenico, orig. p. 108, mistakenly called “San Nicola”)

Bernini’s church in the papal vacation town of Castel Gandolfo (construction 1658-62) was restored in 2011 and on the occasion of the restoration was published La Chiesa di San Tommaso da Villanova. Un progetto di Gian Lorenzo Bernini a Castel Gandolfo. Vatican City: Edizioni Musei Vaticani, 2012. In the course of the restoration, Bernini’s original color scheme for the painting of the exterior was discovered (p. 29) — entirely shades of white (one of them called in the documentation “bianco di travertino”) — hence the restoration brings the church back to its original (though somewhat stark and startling) appearance.

Bernini, Crucifix (bronze), 1654-55, El Escorial, Spain

#43. Regarding the crucifix given by Bernini as a gift to Sforza Pallavicino (Domenico, p. 334, n. 1): it was not of bronze, but of cartapesta!

An exciting discovery in the archives of the Theatine Order in Rome by Prof. Ruben Lopez Conde (University of Jaén, Spain), published in his article, “A propósito del crucificado de Bernini en El Escorial: El crucificado de cartapesta del Cardenal Sforza Pallavicino,” Archivio español de arte, LXXXIV, 335, julio-septiembre 2011, pp. 211-226).

Just twenty days after Pallavicino’s death, the Jesuit cardinal’s good friend, Theatine Father Carlo de’ Tomasi wrote a letter to his brother, Giulio, I Duca of Palma di Montechiaro and future Prince of Lampedusa, reporting that he (Carlo) had received from Pallavicino (shortly before the latter’s death) a gift of a beautiful polychromed crucifix, “modello of Signor Cavaliere Bernino who made a similar one in bronze for our King Philip IV at the request of Signor Ambassador…” (The Tomasi, by the way, were Sicilian aristocracy.) The letter goes on to mention that “Monsignor” [i.e., Pietro Filippo Bernini] had it re-done more than once in order to enhance its vivacity as an object of devotion.” (The letter, in the original Italian, is on p. 218 of the article).

The Carlo de’ Tomasi letter allows no misunderstanding except for the use of the term, modello: does Tomasi mean it in the strict sense? Was he truly informed about the real original status of the cartapesta crucifix? The source of the report about a crucifix gift to Pallavicino is Baldinucci’s Vita which states: “The Cavaliere had made the Crucifix of bronze for His Majesty the King of Spain that we have elsewhere spoken of, and he had made a similar one of it for himself, and while he was in France, he ordered his family to give it as a gift to Cardinal Pallavicino.” (“Aveva il cavaliere fatto per la maestà del Re di Spagna il Crocifisso di bronzo di che altra volta abbiamo parlato, ed un altro simile ne avea condotto per sè medesimo, e mentre si trovava in Francia ordinò ai suoi che lo donassero al cardinal Pallavicino.”)

This passage in Baldinucci has been interpreted — e.g., by Tomaso Montanari in 1997 and 2009 — to mean that the second crucifix (given to Pallavicino) was a full replica in bronze, but the text does not say this explicitly: the adjective, “similar” is rather vague. In his 2009 article, “Bernini per Bernini,” Montanari then identifies this presumed bronze replica with the “large crucifix given to me by Monsignor Bernino” (“Crocifisso grande datomi da monsignor Bernino”) that Pallavicino bequeathed at his death to Roman erudito Stefano Pignatelli. But this passage in Pallavicino’s last will and testament does not prove anything about the crucifix in question, i.e., that it was of bronze and that it was indeed the very same one ordered as a gift by Bernini himself while in France. If it were, I would have expected Pallavicino to be more explicit and say “the crucifix made and given to me by the Cavalier Bernini”. Lopez Conde makes the same observation (p. 217), pointing out that in his will, when referring to other works by Bernini in his collection, Pallavicino is careful to attribute them explicitly and directly to the Cavaliere.

Moreover, knowing how gifts in Baroque Rome were carefully calculated in terms of the recipient’s social rank (as well as personal merit), I myself have always thought it strange that Bernini would give the same huge, and hugely expensive, gift of a “life-size” bronze crucifix that he made for the King of Spain to someone of far inferior rank, i.e., Sforza Pallavicino. Pallavicino was, yes, an influential intellectual and prelate but all indications are that as a cardinal he was not an extremely rich, avidly active power-broker in wordly affairs. (He was a Jesuit living under the vow of poverty in simple Jesuit accommodations at Sant’Andrea al Quirinale). Yes, Pallavicino looked after Bernini’s son during the artist’s absence, but this service and any other that the cardinal might have done for the artist do not deserve such a “magnificent” gift. All the more reason that such a large, costly gift would be grossly inappropriate and improbable for someone of the relatively lowly status of Stefano Pignatelli (d. 1686), the apparent recipient of another bequest from Pallavicino of another large bronze crucifix given to him (Pallavicino) by Bernini: for which see above #50B.

Returning to Carlo de’ Tomasi, the Theatine does not figure prominently in either the Pallavicino or Bernini literature, but Lopez Conde does describe what was in fact a real friendship between Pallavicino and Tomasi, and an not-unsubstantial interaction between Tomasi and Bernini. The interaction between the Bernini and the Tomasi family continued even after Bernini’s death: as we know, in 1722, our own Domenico Bernini wrote the Vita del Ven. Cardinale D. Gius. Maria Tomasi de’ Chierici Regolari.

Entries pre-April 15, 2016 (#1-42) begin here:

#1. To download a scanned copy of the original January 1681 issue of the Mercure galant containing the Bernini obituary

click on this link to the French website, Le Gazetier universel. For further information on the Mercure galante, see the online website, Dictionnaire des journaux 1600-1798, ed. Jean Sgard.

#2. “Bellini, 2002″ cited in n. 13 to the Introduction needs to be added to the Bibliography

Bellini, Eraldo. Agostino Mascardi tra ‘ars poetica’ e ‘ars historica’ Milan: Vita e Pensiero, 2002. This study by Bellini (eminent expert of the intellectual world of Baroque Rome) is the most recent and most exhaustive of the work of Agostino Mascardi.

Likewise add to the Bibliography this article cited on p. 382, n.4:

- Montanari, Tomaso. “Bernini in Francia, visto da Firenze.” Franco Italica 19-20 (2001): 105-33.

Also to add to the Bibliography:

- Petrucci, Francesco. “L’opera pittorica di Gian Lorenzo Bernini,” in Bernini a Montecitorio. Ciclo di conferenze nel quarto centenario della nascita di Gian Lorenzo Bernini, ed. Maria Grazia Bernardini (Roma: Camera dei deputati, 2001), pp. 59-91.

- Zirpolo, Lilian H. “Christina of Sweden’s Patronage of Bernini: The Mirror of Truth Revealed by Time.” Woman’s Art Journal 26 (2005): 38-43 (see photo below).

Bernini’s Mirror for Christina of Sweden (“Truth Revealed by Time”), drawing by Ncodemus Tessin, Jr, who saw the mirror when visiting the queen’s art collection in Rome (drawing in National Museum, Stockholm)

#3. Corrections to the INDEX

Index, p. 464, 1st column: “Arisosto” should be spelled “Ariosto”.

ADD to Index, on p. 471, 2nd column: Boccapianola, Camilla (B’s paternal grandmother), 272, n. 6.

Index, p. 479, 1st column, last line of sub-entry under “Poussin, Nicolas:” “300-101n. 25” should be “300-01n. 25”.

Index, p. 480, 1st column: the 2nd citation of Rossi, Giovanni Antonio de’ is: 415n11, not 315n27..

Index, p. 480, 2n column: The “Santi” of the entry “SS [Santi] Rufina e Seconda” should be “Sante,” i.e., feminine plural. (Please also note that in contemporary documents Santa Rufina is also spelled “Ruffina.”)

#4. Typos and Other Corrections

Page 221 (Domenico, 162): line 8 should read: “with the proceeds of the sale of some of these drawings and modelli, a sufficient” etc. (add “and modelli“).

Page 327, note 43, second-to-last line: Astolfo should be Atlante.

Page 356, note 1: for “Diary of Alexander VIII,” read: “Diary of Alexander VII.”

Page 387, note 16: correct spelling is: magnificentia.

Page 415, note 11: Giovanni Antonio de’ Rossi’s dates are 1616-95.

Page 420, note 14: “December 12” should be “November 12” in both instances.

#5. Pages 12-14 of my Introduction: for further discussion of hagiography in Early Modern Italy

Frazier, Alison K. Possible Lives: Authors and Saints in Renaissance Italy. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

Please note that in my discussion of hagiographic commonplaces (topoi) as found in Domenico, I do not claim that the list of topoi given on pp. 13-14 is exhaustive or that there was only one model of the “saint’s life” in circulation in the seventeenth century.

#6. For further discussion of historiography in Early Modern Italy

Grafton, Anthony. What Was History? The Art of History in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press, 2007.

#7. For new primary-source information on Bernini’s trip to Paris

La Gorce, Jérôme de. “Le voyage du Cavalier Bernin en France, d’après des correspondances inédites.” Confronto: Studi e ricerche di storia dell’arte europea, no. 10-11 (dicembre 2007-giugno 2008) (2007-2008): 63-72.

Among other new primary source documentation, La Gorce prints the text of King Louis XIV’s April 11, 1665 letter to Ambassador Créqui in Rome. He also prints the text of Louis’s letter to Pope Alexander VII (requesting Bernini’s service) as found in the archives of the French government’s department of Affaires Etrangères, which bears the date of April 11, 1665, unlike the copies (from other archives) published by Baldinucci, Domenico, Clément, and Fraschetti, which bear the date of April 18. Among several other new details, the article (p. 65) cites primary source documentation of a stop at Parma by Bernini and his entourage en route to Paris. La Gorce (p. 66) also publishes extracts from a report from the Venetian ambassador, which describes Bernini’s extravagant idea of converting the entire Ile de la Cité into a royal government district, which would have entailed the razing of a massive number of buildings located there.

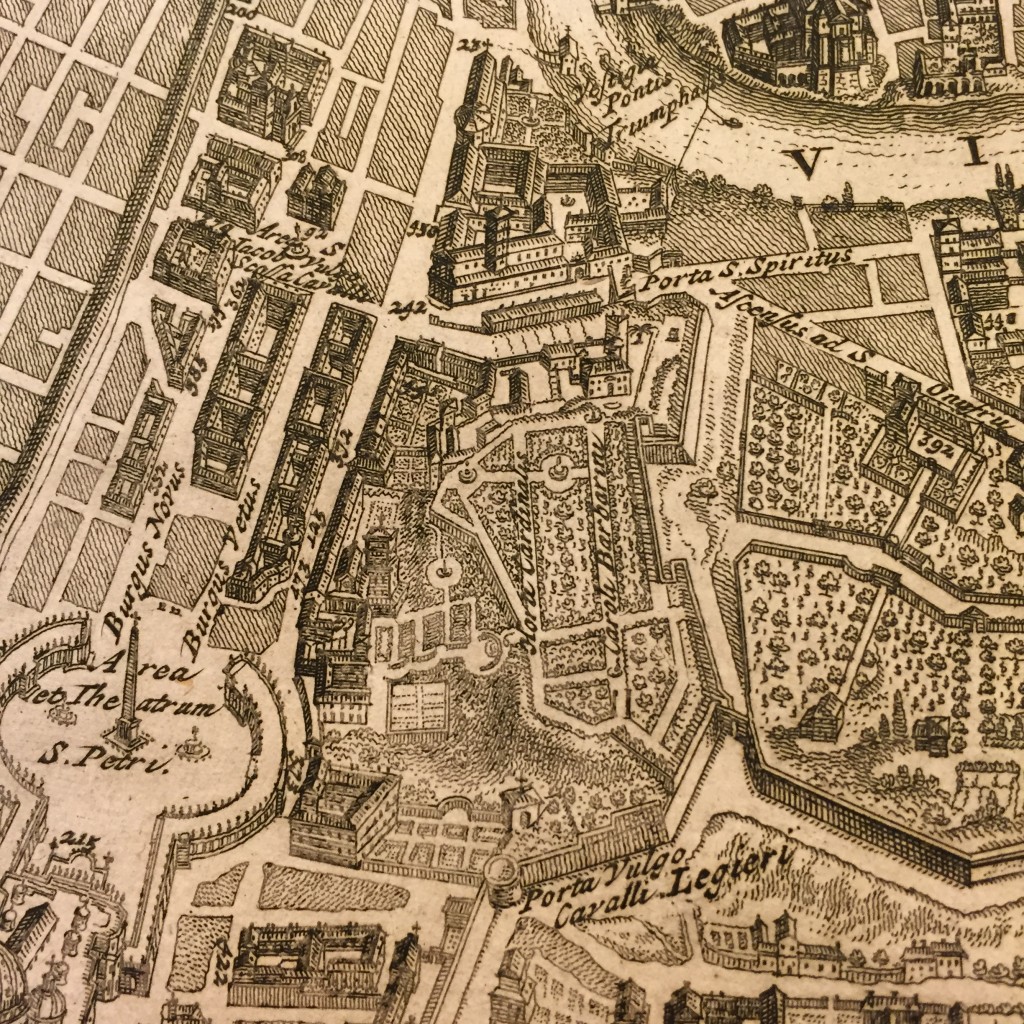

Church of the Feuillants, Rue St. Honoré, Paris, close to the present-day Rue de Castiglione (seen here in an early 18th-century map). This was the church routinely visited by Bernini for ordinary worship during his stay in Paris. It was to become noteworthy during the time of the French Revolution, after which it was demolished.

#8. Bernini’s monumental bronze crucifix commissioned by King Phillip IV of Spain (Domenico, orig. p. 64 and p. 334, n. 1)

Another one of Domenico’s exaggerations: he says ( p. 64) that the crucifix was “larger than life-size” whereas but the corpus is in fact only 4 1/2 feet tall.

An article not cited in my notes by Tomaso Montanari (“Bernini per Bernini: il secondo ‘Crocifisso’ monumentale.” Prospettiva 136 [2009]: 2-25) adds new, illuminating data as well as correcting some minor errors of past scholarship.

The article also discusses other related bronze crucifixes, e.g., the replica of the Spanish crucifix that Bernini created for his personal use (eventually giving it as a gift to Cardinal Sforza Pallavicino) and a similar crucifix commissioned by Cardinal Antonio Barberini, Jr. in Paris. Contrary to what until recently was believed, Barberini commissioned that crucifix for himself, not as a gift for King Louis XIV of France (who received it only years later as a postmortem bequest by the cardinal’s heirs). As for the Sforza Pallavicino gift-crucifix, Montanari argues that it corresponds to the one now in the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. Montanari, furthermore, hypothesizes that Bernini had originally created that crucifix as a form of artistic self-defense in the wake of the embarassing “dethronement” by King Philip of his crucifix (for reasons unknown) from its place of honor in the mausoleum of the Spanish kings at El Escorial.

UPDATE: SEE ITEM #43 ABOVE regarding discovery by Prof. Ruben Lopez Conde — that the crucifix received as a gift from Bernini by Pallavicino was in reality one of cartapesta (papier mâché), not of bronze.

UPDATE: SEE ITEM #50 ABOVE: Charles Scribner’s newly published article, See Charles Scribner III’s newly published “Imago Christi: Bernini’s Saviors, Lost and Found”

On the El Escorial crucifix, now see (an article I have not yet have had time to read):

García Cueto, David. “Sobre el encargo y envío a España de los Crucificados de Gian Lorenzo Bernini y Domenico Guidi para El Escorial.” In Los crucificados, religiosidad, cofradías y arte. Actas del simposio 3/6-IX-2010, edited by Francisco Javier Campos, 1081-99. El Escorial: Real Centro Universitario Escorial-María Cristina, 2010.

***

As to the attribution of the Toronto crucifix, not all scholars are in agreement with Montanari that it is indeed a work by Bernini. Charles Scribner (personal communication, June 25, 2011) has written: “[L]et me go on record as saying, with as much regret, that [the Toronto crucifix] is not by Bernini. It surely derives from his crucifix for Philip IV — or from the still lost copies he made for himself and for Barberini — but not by Bernini himself. It lacks his distinctive tension and persuasiveness; too attenuated and ‘pretty’; today it might be described as ‘Bernini Lite.'” (Scribner, I might add, is author of one of the most useful, best written, and best-selling introductory books on the art of Bernini: Gianlorenzo Bernini, New York: Abrams, 1991.)

***

Update from Charles Scribner, April 14, 2012 (personal communication):

“The museum’s condition report — specifically, that the bronze was cast in 5 or 6 separate pieces — solves, for me, the central paradoxical puzzle: namely, that parts of that highly finished bronze crucifix appear an exact, slavish copy of the Bernini original in the Escorial [something he himself never did and would never do, as he explained to Chantelou] yet others [drapery, exaggerated feet and spindly legs] seem so arbitrary and utterly lacking in Bernini’s ‘handwriting’. Solution: the Toronto bronze is a later casting and assemblage, not overseen by Bernini himself, comprising perhaps the original cast of the head and torso [hence an almost exact copy of the Escorial original [the differences would be due to final chasing]; if not the original cast, then perhaps one based on the original model] and added limbs and drapery, from new casts, meant to ‘complete’ the Bernini head and torso. Bottom line: it’s an intended ‘replica’ of the Bernini original, finished with loving care by a pro, with added flourishes of detail meant to to be Plus-Bernini, but not by the maestro himself.”

Further update (April 19, 2016): the discovery by Prof. Ruben Lopez Conde — see item #43 above — that the crucifix received as a gift from Bernini by Pallavicino was in reality one of cartapesta (papier mâché), not of bronze, strengthens Dr. Scribner’s argument that the Toronto crucifix does not come from the hand of Bernini.

#9. Regarding Bernini’s bust of the Savior

(See also the Update above #56bis)

Domenico (p. 225) describes the pose as “our Savior in half-figure …with his right hand slightly raised, as if in the act of imparting a blessing.” Like most people, I have simply understood the gesture as a blessing, pure and simple. However, as Charles Scribner explains in an article that has recently come to my attention, the issue is more complex and offers some clarification:

“The unusual gesture — clearly no simple blessing — that [Irving] Lavin interpreted as ‘an ambiguous gesture of abhorrence and protection’ may more precisely , I submit, refer to the Noli me tangere of Saint John’s Gospel (20:17), the first appearance of the resurrection Christ to Mary Magdalene. . . . Evoked through Christ’s upturned eyes and raised hand — an aloof, cautionary benediction — Bernini’s biblical allusion would have been reinforced by the angels [of the intended but never executed pedestal] that, with hands covered, raised the divine effigy above the touch of mortals…. Considered afresh in its original context, as a sacramental apotheosis, the Savior may finally come into focus” (Charles Scribner III, “Transfigurations: Bernini’s Last Works,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 135.4 (1991):490-509, here 507.

NOW AVAILABLE ONLINE IN DIGITAL FORM VIA “scribd.com”:

Bernini: His Life and Works

BY Charles Scribner III

http://www.scribd.com/doc/

Bernini’s final (and recently rediscovered) sculpture: Bust of the Savior (1679), San Sebastiano in Via Appia (photo courtesy of Charles Scribner III)

Dr. Scribner has kindly sent me an advance copy of his entry on the bust of the Savior that will be included in the forthcoming new edition of his book on Bernini:

BERNINI’S REDISCOVERED LAST & LOST MASTERPIECE

Bust of the Savior

1679-80 Marble, height 106 cm.

San Sebastiano Fuori le Mura, Rome

In his final sculpture the eighty-year-old maestro “summarized and condensed all his art,” Domenico Bernini wrote, adding that his father’s “bold conception” more than compensated for the “weakness of his wrist.” Bernini undertook this parting work not for his own tomb, a marble slab in Santa Maria Maggiore, but as a gift for Rome’s preeminent Catholic convert, Queen Christina of Sweden. When she refused to accept it, saying she could never afford to repay Bernini for its true worth, he bequeathed it to her. On his deathbed he asked for Christina’s prayers since she shared “a special language with God.” It was precisely through Bernini’s special language of gesture and facial expression that his otherworldly “speaking portrait” of the Lord communicates its meaning.

The bust was originally mounted on a round Sicilian jasper base and supported by two angels kneeling on a gilded wooden socle. Bernini’s sketch (Museum, Leipzig) for the pedestal reflects his drawing (also in Leipzig) of similar angels elevating a monstrance to display the sacramental Body of Christ. Bequeathed by Christina to Innocent XI, Bernini’s Savior was later adapted as the official emblem of the Apostolic Hospital in Rome before vanishing in the early eighteenth century. Only a preliminary drawing preserved Bernini’s redeeming image until Irving Lavin published in 1972 the marble in Norfolk, Virginia, as the lost bust. This was followed a year later by the discovery, in the cathedral of Sées, of the copy commissioned by Bernini’s Parisian friend Pierre Cureau de la Chambre. While the latter bust reveals a classical beauty and polish typical of a competent copyist, the Norfolk version, on the other hand, appears almost Gothic by comparison, and it remained puzzling–even if accepted by most scholars. The recent rediscovery, four decades later, of the lost original in the sacristy of San Sebastiano Fuori le Mura in Rome confirms—as Lavin himself attests–that the Norfolk bust is in fact a copy (perhaps dating from the late 18th century); the bust at San Sebastiano, now brilliantly displayed in a grand niche in the basilica proper, reveals in full glory Bernini’s magnificent sunset in marble. It is well worth the pilgrimage along the Appian Way.

Clearly no simple blessing, the unusual gesture that Lavin interpreted as an ambiguous combination of “abhorrence and protection” may, more precisely, refer to the Noli Me Tangere — the first appearance of the resurrected Christ to Mary Magdalene: “Do not touch me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father” (John 20:17). Evoked through Christ’s aloof visage and raised hand — an unexpectedly cautionary benediction — Bernini’s biblical allusion would have been reinforced by the angels that, with hands covered, lifted the divine effigy above the touch of mortals. When designing a symbolic globe to raise his Louis XIV in a royal apotheosis, he explained that its practical function was to prevent viewers from touching the bust. Considered afresh in its original context, as a sacramental apotheosis, the Savior may finally come into focus. The features that seem exaggerated up close, together with the tumultuously abstracted drapery folds and the blank eyes of classical Roman portrait busts, are resolved into an expression of enormous spiritual intensity when viewed from below. Its concetto is emphatically Eucharistic — a huge white Host elevated as “the Bread of Angels.” This is Bernini’s marble sacrament, raised in his last labor of adoration.

According to his biographers, Gianlorenzo’s career commenced with the posthumous bust of Bishop Santoni, a public effigy; seven decades later, it concluded with a private bust of the Eternal Savior, animated through marble folds that follow no natural pattern. The striking realism of the child prodigy was transfigured, in the end, by the ethereal vision of a genius for whom life and art were as inseparable as fact and faith.

—Charles Scribner, Bernini (revised 2014 eBook edition)

#10. Update July 2023: The Goat Amalthea is NOT by Bernini

One of the results of the monumentally comprehensive Bernini exhibit of 2017 at the Galleria Borghese — which placed so many of his sculpted works side by side for close comparative analysis — was to cast great doubt upon the Bernini authorship of the small marble piece in the Borghese Gallery, The Goat Amalthea which had long been considered the earliest work by the young Gian Lorenzo (see my Domenico note, p. 279, n. 13). In fact, the Gallery has removed the Bernini attribution, giving the work to an anonymous sculptor. Former director of the Borghese and co-editor of the new “catalogo generale” of the gallery (vol. 1, Officina Libraria, 2022) Anna Coliva discusses the detailed stylistic and technical reasons for this (the work is completely unlike any other work by Gian Lorenzo) in a recent article (July 2023) in the online art journal, aboutartonline.com

Here is the Coliva entry on the Capra Amaltea in vol 1 (cat. 41) of the 2022 Catalogo generale of the Galleria Borghese, edited by Coliva. Note that the only Baroque source to attribute the work to Bernini is Joachim von Sandrart in 1675, an attribution not given any scholarly credence until 1926 by Roberto Longhi.

this is my originally posted entry on the Goat Amalthea:

An English translation of Rudolph Preimesberger’s essay on Bernini’s The Goat Amalthea with the Infant Jupiter and a Satyr (first published in 2002 in Bernini scultore, ed. A. Coliva)

is now available in the recently published collection of his essays, Paragons and Paragone (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute Publications Program, 2011). Still considered virtually universally as Bernini’s first independent work of sculpture, it is discussed in my Domenico edition on p. 279, n. 13. I would add to that note the fact (cited by Preimesberger, 2011, 54) that contemporary writer and artist Joachim von Sandrart describes the work as Bernini’s “first famous work” (“sein erst berühmtes Werk”), attesting to the success of the sculpture as a paragon of overcoming the “difficultas” of treating such a theme in marble.

#11. For more on Filippo Maria Bonini and his L’ateista convinto dalle sole ragioni (Venice, 1665),

cited on p. 314, n. 27 and p. 414, n. 9 (for criticism of Bernini’s work on the Four Piers of St. Peter’s), now see: Tomaso Montanari, “Roma 1665: il rovescio della medaglia. L’ateista convinto dalle sole ragioni dell’abbate Filippo Maria Bonini,” Ricerche di storia dell’arte 96 (2008): 41-56. Bonini’s book, ostensibly a series of dialogs between an open-minded atheist and a convinced Jansenist, is actually a vehicle for Bonini to deliver biting satires of various aspects of contemporary Rome, especially the world of the Roman (papal) court and of the art world in its multiple dimensions.

#12. To the bibliography cited in note 23 on page 422 regarding Bernini’s various busts of Pope Clement X Altieri (mid-1670s)

add the good, succinct, thorough discussion by Lisa Beaven, “Bernini’s Last Papal Portrait and its Audience: The Statue of Pope Clement X Altieri,” in The Italians in Australia: Studies in Renaissance and Baroque Art, ed. David R. Marshall, 95-106, Florence: Centro Di; Melbourne: The Membership of the Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne, 2004.

Bernini, Pope Clement X Altieri, formerly Palazzo Altieri, now Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome (photo: Wikimedia Commons)